The following blog post by Murray McLean originally appeared on his blog 'The View from Westrigg: Little Histories of Modern Scotland'. It is an adapted version of a work-in-progress presentation he gave at the seminar ‘Some issues on marriage and divorce’, which took place on 11 December 2017 at the School of Law. The article is a potted history of the development of the categories used in marriage registration in Scotland, followed by a speculative exploration of some of the issues this may represent in contemporary Scottish society.

You can read more of Murray's writing at: https://theviewfromwestrigg.wordpress.com

Recent decades have seen major diversification in the contexts – both institutional and commercial – within which couples can exchange matrimonial consent in Scotland. Civil weddings can now take place in any approved venue, and ‘belief’ as well as religious organisations can register marriage celebrants. This proliferation of ‘denominations’ raises an important question: if couples consent to a single concept of marriage under Scots law, what is the significance of the diverse means by which they are permitted to do so? Using registration data held by the National Records of Scotland, this paper explores the popular meanings attached to legal categories, and attempts to outline the practical implications of liberalising legal wedding provision.

*

Every marriage registered in Scotland is assigned a denomination. In the language of civil registration, denomination has a broader meaning than in everyday speech: it denotes the organisation represented by the marriage celebrant. So, counter-intuitively, ‘civil’ is in fact considered a denomination for registration purposes (or rather it is several denominations, depending on whether it refers to a registry office wedding or one another kind of approved venue).

There is no statutory prescription of the relationship between the denomination of the wedding and the nature of the marriage is solemnises: a Methodist wedding, for example, need not create a Methodist marriage, because in the eyes of the law there is only marriage. What the denomination does indicate, however, is what I’m going to refer to as the context for consent: the setting within which consent to marry is exchanged. It gives some clue as to the look and the location of the ceremony, and in a broader sense it might indicate something about the definition of marriage at work in a particular wedding, whether the couple or just the celebrant subscribe to this.

From a historical perspective, the obligatory inclusion of denomination for registration purposes is a hangover from the history of denomination in the theological sense of the word. Different countries have taken different routes towards recognising a variety of beliefs in the solemnisation of marriages. In France and Germany, for example, only civil marriage is legally valid, but the civil ceremony may be followed by religious rites of the couple’s choosing. In Scotland, the opposite approach has been taken, gradually extending legal recognition to the ceremonies of an ever-growing number of religious – or more recently, ‘belief’ – organisations.

I’d like to argue, however, that over the course of the twentieth, and twenty-first centuries, the reality of this inclusive agenda has altered significantly. Over the past decades, a tension has emerged between the legal recognition of existing organisations, and the creation of new ones more narrowly geared towards providing weddings and other ritual services.

It is in this context that I use the term ‘liberalisation’ with regard to legal wedding provision. The recognition of new denominations is no longer a question solely of granting equality to previously marginalised communities. The law doesn’t define either community or belief too strictly: this is probably as it should be, but it also means that the mechanisms for inclusiveness in wedding provision can also be put to somewhat creative use. This can be a means of bypassing conventional definitions of community, and in this sense it might be an update of the toleration agenda for the postmodern age. But there is also the potential for simple entrepreneurialism.

I’ll unpack these arguments a bit later on: the bottom line for now is that weddings can legally be solemnised by any organisation that fits the fairly loose criteria of representing a group united by a religion or other belief. In contrast to the legislation that allowed, for example, Catholics or Jews to marry legally by their own ceremonies, the contemporary mechanisms for recognition cater more to organisations than to communities as traditionally defined. The aim of this paper is to assess the practical implications of the law in this regard, and to pose the question of whether it may be time to rethink its function in marriage formation.

*

Before I move onto some specific case studies, I’ll begin with an outline of the recent history of weddings in Scotland, in both legal and cultural terms. The aim here is to show not just how the law has shifted towards liberalisation, but also how popular practice has undergone its own evolution, often with only an indirect or instrumental relationship to the law.

The Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977 is really the cornerstone of the developments I’m discussing here, but I’d like to start with the 1939 Act. These two Acts bookend the mid-twentieth century history of marriage and Scotland. In both a legal and a cultural sense, this is a fairly distinct historical period.

The 1939 Act abolished marriage by declaration in 1940, and introduced civil marriage. Combined with unprecedented marriage rates and the falling average age at marriage, this made the period one of overwhelming uniformity. Civil weddings could only be performed in a registry office, in contrast to the theoretically endless possibilities with marriage by declaration. Interestingly, religious weddings also became restricted to one venue, the Church: this happened, however, not by law, but apparently by preference: couples were still able to marry at home, in commercial venues, or in the manse as they had done in huge numbers before and during the Second World War, but they no longer did. At the same time, these newly universal church weddings began to look very homogenous, with the classic white dress taking on a new dominance. These middle decades thus abolished the legal ambiguities of irregular marriage, and simultaneously, the culture of weddings abolished any ambiguity around the rituals of marriage themselves. More than ever before, the wedding day was marked out as special, different in every way from everyday life and other special occasions. In a sense, the law supported this, by demanding some contact with the state or a religious institution: marriage had to be ceremonial by default, even if that was the low-key ceremony of the register office.

This was also a period when the differences between different denominations were fairly well demarcated. This happened at the level of material culture: the white wedding was a religious phenomenon, and it would be the mid-1970s before big white dresses started cropping up in registry offices. It was also true at the institutional level: even the Church of Scotland, which claimed to cater to all parishioners regardless of their beliefs or affiliations, imposed certain requirements on those it married, particularly divorcees, implying that a religious wedding was to some extent conditional on a commitment to religious marriage. In some cases, this relationship between wedding denomination and personal belief or behaviour was in fact supported by the law: Jewish and Quaker weddings could only be legally recognised as such when both parties to the marriage (or at least one party in the case of Quakers) was formally a member of the religion in question. This requirement remained in place until the 1977 Act.

I don’t want to overstate the idea that the denomination was prescriptive in mid-century marriage. A major counterpoint to this suggestion is the fact that civil marriage in Scotland never involved any requirement to state one’s rejection of religious marriage. Until the 1940s, that had been the case in England and Wales, where civil marriage had been introduced in the mid-nineteenth century. Nonetheless, relative to the present, the middle decades of the 20th century were characterised by a tighter policing of denominational distinctions with regard to the meaning of marriage, and these operated at the levels of popular culture, institutional authority and, in some cases, even the law itself.

*

If the mid-twentieth century was a distinct period in the history of weddings in Scotland, the 1977 Act more or less marked its end. The major innovation with regard to contexts for consent was that it created a relatively open system for nominating new religious marriage celebrants. Under the terms of section 9 of the Act, religious organisations could nominate celebrants to be registered to perform marriages, and it was up to the Registrar-General to decide whether the organisation in question qualified as a religious body. In addition, Regulations following the Act named the 12 religious bodies that would be permanently registered. I think it’s worth stressing that the Act facilitated the registration of celebrants, not of organisations, but marriages still had to be registered with the denomination rather than just the name of the celebrant recorded. This relatively open system of registration thus still relied on the assumption that institutional context was required for the exchange of consent to marry.

However, many of the new denominations were not exactly institutions: the permanently registered denominations included bodies like the Church of Scotland, the Roman Catholic Church, the Congregational Union of Scotland; after 1977, however, there was a proliferation of bodies such as the Maranatha Centre in Motherwell, or my own local Bathgate Community Church. These were Christian organisations essentially serving one local community or congregation and not obviously belonging to any denomination in the theological sense of the word.

Some of the new developments, however, were more in line with the older pattern of extending recognition to existing faith communities: the late 1970s and 1980s saw the first legally recognised Muslim, Hindu and Sikh weddings. Each of these faiths was, however, composed of various individual denominations based on local faith organisations: for example, it was Glasgow Central Mosque and the Fife Islamic Centre in Kirkcaldy, among others, whose celebrants were recognised, rather than the Muslim faith in Scotland per se. It’s probably not insignificant that an amendment to the 1977 Act in 1980 added section 23A: this strengthened the protections first introduced in 1939, which ensured the validity of a registered marriage that met the basic criteria of a valid exchange of consent even when aspects of the ceremony were lacking or the celebrant was unqualified. In the context of a fairly rapid expansion of the number of denominations, it made sense to give a baseline guarantee to couples marrying in relatively untested organisational contexts.

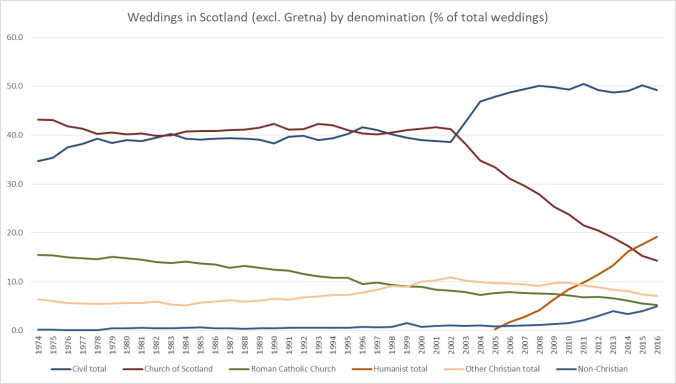

Figure 1 (Source: National Records of Scotland)

In terms of the overall denominational profile of marriage in Scotland, the 1977 Act did not make a huge impact (see figure 1). Even though new denominations were continuously registering celebrants, the actual number of couples married by these organisations, even for the newly recognised major faiths, was fairly small. In terms of the culture of weddings, the major development in this period was really a redoubling of the strength of the white wedding ideal: in fact, it was no longer solely associated with religious marriage, and the white registry office wedding became a more common sight. This might seem like a fairly obvious development, but I think it says something significant about the meanings attached to different legal denominations: the strict delineation of civil and religious marriage in popular culture seemed to be eroding, and a more homogeneous ritual culture around weddings developing in its place. In that culture, the legal categories applied to weddings seemed to matter less than the cultural meanings of ritual and symbol.

The next piece of legislation that seemed to have a major impact on popular practice was not in fact Scottish legislation. From 1995, couples marrying in civil ceremonies in England and Wales were able to marry outwith the registry office in so-called Approved Premises, which allowed greater aesthetic freedom and no doubt also greater commercial involvement in civil weddings. It was accompanied by an immediate upswing in rates of civil marriage south of the border. It was 2002 before comparable legislation was introduced in Scotland, but on the ground the impact of the English and Welsh law was in fact visible here as well. Photos published in local newspapers suggest that, after years of ubiquitous church weddings, Scottish couples were suddenly returning to the earlier practice of marrying in hotels or other hired venues. Whether this was emulation of English and Welsh wedding culture, or part of a cultural moment to which only England and Wales had responded legislatively, it would appear that Scottish couples used existing Scots law to enact the liberalisation brought about by legislation in other countries.

What these developments on both sides of the border show is the increasing importance of wedding celebrations beyond their legal specificities: the promise of a freer choice of venue attracted many English and Welsh couples away from religious marriage; in Scotland, even if didn’t win people back to the churches, the existing freedom of choice in religious marriage didn’t do any harm to their somewhat surprising longevity as wedding providers. When Scotland did introduce Approved Premises for civil weddings – although here they were actually called Approved Licensed Venues – there was the first major increase in the rate of civil marriage since the 1970s (see figure 1), further underlining the importance of the aesthetic or ritualistic as opposed to legal or administrative elements of the wedding.

The final major phenomenon in legal wedding provision I’m going to touch on is the advent of the Humanist wedding. The Humanist Society of Scotland (HSS) was permitted to register celebrants in 2005, meaning it rather ironically had to be recognised as a religious body. This anomaly was addressed by the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014, which introduced the category of belief bodies alongside religious bodies: organisations nominating celebrants no longer had to demonstrate a religious purpose, but the somewhat vaguer quality of a shared belief. We are still in the very early days of this legislation, but it seems to be having some interesting consequences. A lot of people have pointed out in the past year or so that Humanism is the single largest denomination for weddings in Scotland, other than civil, but HSS themselves have been quick to correct this. There are now various Humanist wedding providers whose celebrants are registered as representing distinct denominations to HSS, and only taken together do all of these weddings constitute the largest denomination. This is a significant development. HSS is fairly well represented across Scotland, and was still growing as a denomination when the other providers emerged. In that context, I find it hard to see this as anything other than commercial competition. It suggests that the introduction of belief weddings, while clearly a logical development, may be opening the door to a kind of liberalisation that was not the initial intention.

*

I’m now going to look at a couple of case studies to illustrate some of the points raised in this potted history in more depth. I’ll return to the case of Humanism in a moment, but first I’d like to focus on Gretna.

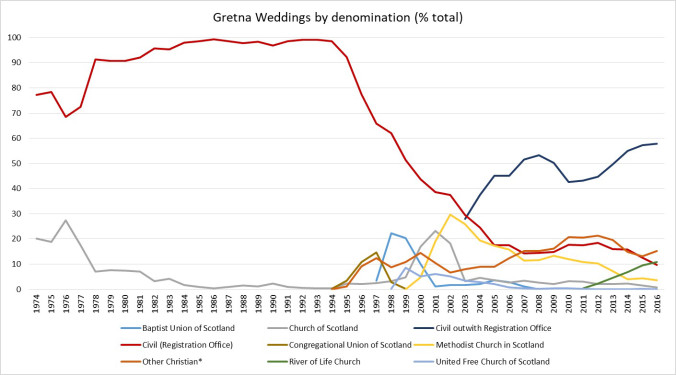

Figure 2 (Source: National Records of Scotland)

I have removed Gretna from my general statistics on Scotland, because it seriously skews the data. Since about 1993, over 10% of all weddings in Scotland have taken place at Gretna, and the figure was closer to 20% in some years. The reason this is particularly problematic is that the vast majority of people marrying there are not resident in Scotland, and the profile of these marriages in terms of denomination is significantly different to the rest of Scotland. Until the mid-1990s, virtually all weddings at Gretna took place in the registry office (see figure 2). It was only with the introduction of Approved Premises in England, where most of those marrying at Gretna were actually resident, that other denominations began to be better represented. Again, it’s hard to interpret this as anything other than a matter of picking the right venue: as English couples at home were opting en masse for civil ceremonies in commercial premises, those who came north to get married were suddenly having church weddings. Just like the Scottish couples returning to the hotel weddings of earlier decades, ‘wedding tourists’ were, in a sense, using Scots law to liberalise practice ahead of the liberalisation of the law. The timing of this suggests that it wasn’t a newfound knowledge of Scots law that underlay the choice of English couples, but simply their expectation that a variety of venues would be available to them.

No single denomination dominated this new market for religious weddings: the Baptist, Congregational, Methodist and United Free Churches, as well as the Church of Scotland, all had brief periods of popularity. There was also steady growth in the churches I’ve grouped together as ‘Other Christian’: I haven’t investigated each of these in depth, but they seem to be small organisations, or branches of international evangelical or charismatic churches registered in Scotland after 1977. I’ve singled out the most popular of these, the River of Life Church. It now accounts for about 10 per cent of Gretna weddings. A quick look at its website shows that it operates only in Dumfries and Galloway, and mainly at Gretna, but it does seem to be part of a wider network of similar churches. In the information about marrying, they’re very keen to state that couples won’t be subjected to any sort of religious examination: in fact they seem to imply that couples aren’t even expected to be religious in order to marry there. It probably goes without saying, but it seems that the vast majority of people married by the River of Life church at Gretna probably couldn’t be described as congregants.

The introduction of Approved Licensed Venues for civil marriage had the same effect in Gretna as elsewhere, with a big upswing in the rate of civil marriage. Interestingly, this seems to have ended the brief popularity of Gretna’s older Christian churches, but the smaller, newer Christian denominations continued to grow in popularity. Again, I’m only speculating at this stage, but I think this suggests that these churches took root in Gretna mainly in response to the wedding tourism market there, as similar organisations have been nothing like as popular in most of the rest of Scotland.

What Gretna shows quite clearly, then, is that the choice of denomination can be fairly instrumental: it’s the ritual that matters, and choosing a religious over a civil wedding in this context can be a means to an aesthetic end. Significantly, however, the introduction of Approved Licensed Venues didn’t reverse the trend towards religious marriage, but simply added another serious contender to an emergent free market in marriage provision. There was clearly still some appeal to marrying by religious rites, even if quite demonstrably for many couples this was not a matter of marrying in the specific faith of their family or community.

*

I’ll return to the Humanists now, because I think their case sheds some more light on what’s going on at Gretna and in Scotland more generally.

When Humanist weddings were first legally recognised, the demographic profile of the couples involved diverged quite a bit from the Scottish average – they were older, more likely to have been previously married, and more likely to have been born or be resident outside Scotland than the average. After a few years, and as their numbers increased, however, these figures converged with the Scottish average. What this suggests to me is that Humanism was at first recognised in a way similar to what happened with Islam in the 1970s or dissenting Protestant denominations in the nineteenth century: it was an existing community marginalised by the mainstream and subsequently welcomed by inclusive administrative practice and, ultimately, legislation. The demographics of Humanism diverged from the average because they represented a distinct community. Subsequently however, Humanist couples became indistinguishable from the average.

I think what this suggests is that Humanism now functions more along the lines of the small Christian organisations at Gretna, catering to those who want a religious or belief wedding but who aren’t necessarily card-carrying members of the organisation. HSS does ask couples to join the society when they marry, but I think they themselves would happily recognise that many of the couples who approach them aren’t already committed Humanists. This trend towards Humanism as a popular alternative rather than a distinct belief community is confirmed by the emergence of rival Humanist wedding providers. Given that there aren’t denominations of Humanism in the theological sense of the word, and given HSS’s decent geographical representation in Scotland, the new Humanist providers don’t seem to be meeting any particular need other than a market’s need for competition. They seem to have been successful among younger couples, and their geographical spread seems to be more in line with the resident population of Scotland: for example, there are proportionally more new Humanist weddings in places like North and South Lanarkshire, and fewer in the Highlands compared to those performed by HSS.

Having said that Humanist demographics converged with the average, I should point out that those marrying in all the Humanist denominations are now in fact younger on average than other couples. I don’t think, however, that this represents a distinctive Humanist demographic: in fact, they now most closely resemble the profile of Church of Scotland marriages. This is really quite significant. Historically, the Church of Scotland’s main competitor in wedding provision has been civil marriage, but since about 2007, the growth of Humanist weddings has been directly proportionate to the decline in Church of Scotland weddings. It may be premature to speculate on these things, but I think what we’re seeing is the emergence of Humanism as a third default choice for the average couple with no particular institutional affiliations. In the same way that the Church of Scotland played what it called a territorial role, catering to local people regardless of belief, and registrars were theoretically available by law in every district, Humanism is now a ubiquitous wedding provider. Its appeal is that it offers not just a personalised service, but also the charismatic appeal of belief, a sense of deeper meaning, however without enquiring to closely into the beliefs of couple’s themselves. Civil marriage now offers a similar level of individualisation to Humanism – in fact, in the past few years it has been permitted to include religious elements in a civil ceremony so long as they are not performed by the registrar. However, civil marriage still suffers from historical connotations of drabness and even secrecy: not to mention the years of centralisation in local government that has drastically reduced the number of registration districts and therefore the legally required minimum number of registrars. Humanism may be emerging as a successor, at least in cultural terms, to civil marriage.

*

To return to the questions I set out at the start of the paper: what is the meaning of denomination, and what function is the law fulfilling in the way it uses this category? What I’ve tried to show is that the meaning of denomination has undergone significant evolution over time: the law has recognised this partly, first by creating an open system of registration for celebrants and more recently by extending the definition of denomination to include belief as well as religion. The most marked evolution, however, has been in popular practice, and it is not clear that the law has totally kept pace with this. In recent decades, denominations have become subject to what we might think of as a kind of ‘forum shopping’: it is no longer so much the religious or other beliefs represented by a particular organisation that matter to couples as their facilities, geographical coverage, and the flexibilities accorded to them by the law. The recognition of belief organisations and, in particular, how this has played out with Humanism, highlights, I believe, the extent to which the law is facilitating not only a free market of beliefs, but also a literal, commercial free market in wedding provision. This is what I mean by the liberalisation of legal wedding provision.

In itself, this doesn’t have to be a bad thing. In practical terms, it does mean that the law is meeting the needs of lots of couples: the practice of recognising celebrants only as representatives of organisations may not fulfil the logic of inclusion that was once its rationale, but nor does it deprive couples of the flexibility to choose a ceremony that suits them – as long as they have the money. And indeed, everything would seem to suggest that it is these ritual elements of marriage, such as the venue, the clothes and so on, that matter most to most couples. There’s another major indication of this in the case of same-sex couples converting their civil partnerships to marriages: about 97% of these conversions have been registered as registry office ceremonies, which most likely indicates that the conversion was by the ‘administrative route‘ rather than involving any actual ceremony, as the two are not distinguished in registration statistics. For these couples, however they celebrated their civil partnership was the meaningful ritual in their relationship, even though the law strictly speaking envisages merely the registration of such a partnership rather than its ceremonial solemnisation as with marriage.

It is in this crucial area of ritual that legal and popular understandings of denomination are liable to come into conflict. From the perspective of popular practice, denominations are in fact wedding providers: their celebrants are ritual specialists, and society being what it is, this commonly means that they sell ritual. Churches and charities such as HSS may feel a moral obligation to keep these costs down, but there is little in the way of parallel legal obligation. A celebrant may have registration revokedif they have quote “for the purpose of profit or gain, been carrying on a business of solemnising marriages”, but the solemnisation itself is hardly the only part of the wedding liable to involve expense. This is not exactly a catastrophe at present, but I do think it’s worth being alive to the potential for abuse of the system as it is currently developing. At the moment, couples still seem to be benefiting from the liberal approach to denominations: but the nature of the law is that organisations rather than communities are empowered and recognised. It may be that community is no longer an adequate category for conceptualising the needs of couples with regard to wedding provision: if this is the case, it may be time to envisage a new way of placing couples at the heart of the law on marriage formation, in principle as well as practice.

On that note, just one final speculative point: civil marriage was introduced not to create a denomination for unbelievers, but to try and ensure that couples weren’t missing out on the protections of property law and social security. The law tries to do the same thing now, mainly through developing the rights of cohabitants, but marriage still remains the main channel for securing those protections. If ritual in a generalised sense now means more than religious or other rites, the thing stopping couples marrying may not be so much principled objection to the institution as the prohibitive costs of ritual. Indeed, sociologists have been pointing this out, particularly in the USA, for quite a few years now. With this in mind, an inclusive law of marriage formation would not only look to the beliefs of various individuals and communities, but also to their socioeconomic condition. It may be time to start taking ritual consumption seriously… might it even be time to start thinking about wedding boxes as well as baby boxes?

~ Murray McLean

Murray McLean is a PhD student at the University of Glasgow, currently researching marriage and weddings in Scotland since 1945.

You can find him on Twitter: @McLeanMurray